A good end for ‘The Good Wife’

DO NOT READ THIS POST (OR LOOK AT IMAGE ABOVE) IF YOU INTEND TO WATCH THE GOOD WIFE S7 E22.

My chosen method of coping with the hideous, disastrous events of Friday was not to resort to alcohol or other mind-numbing substance, but rather to retreat into the fantasy-yet-still-very-real world of The Good Wife. Here too something wonderful, something that promised hope, was coming to an end, with the final episode of series seven. When this was screened six weeks or so ago in the States, I did my level best not to read the tributes and obits and social media scraps, and so I came more-or-less fresh to my time-shift of Thursday’s More4 broadcast.

This is a series I was alerted to by stumbling across an episode on a plane half a lifetime ago, and which I’ve now seen every episode of, almost all of them with my wife Clare. I have marvelled at its narrative invention, its topicality, its progressive politics, its reinvention of the legal drama (especially important to me as a long-time L.A. Law fan), and its brilliant cast of characters (hard to say if Eli or Kalinda has been my favourite after Alicia herself).

Unlike many others I was far from disappointed by S7 E22. The episode had a pleasing circularity for those of us who have been there (more or less) from the start. It had one last Machiavellian manoeuvre from Eli. It had Will back from the dead (“I’ll love you forever.” “I’m good with that.”). It had tears and laughter and one of the best eccentric judges and impeccable dress sense and ample ambiguity. And it had that final frames slap, followed by a newly assertive Alicia walking with confidence (maybe) into a bright (maybe) future. (Please, for all of her uncertainties, can we slough off our even-greater ones, and go with her?)

Both in the States and here, however, the final show was regarded as somehow falling short of the impossibly high standards that the series has managed to sustain despite a punishing 22-episode output across seven years. So just what, I wondered, was the problem? For Jonathan Bernstein at the Telegraph, who reminds us of great series finales from the past,

the Kings [co-creators Robert and Michelle] had done almost nothing to earn that symmetrical slap [Alicia slapped Peter in S1 E1]. The show’s final two seasons were a jumble of unfinished plotlines and unmotivated actions, but Alicia Florrick remained a constant oasis of good sense amid the chaos.

Brian Moylan for the Guardian was more positive:

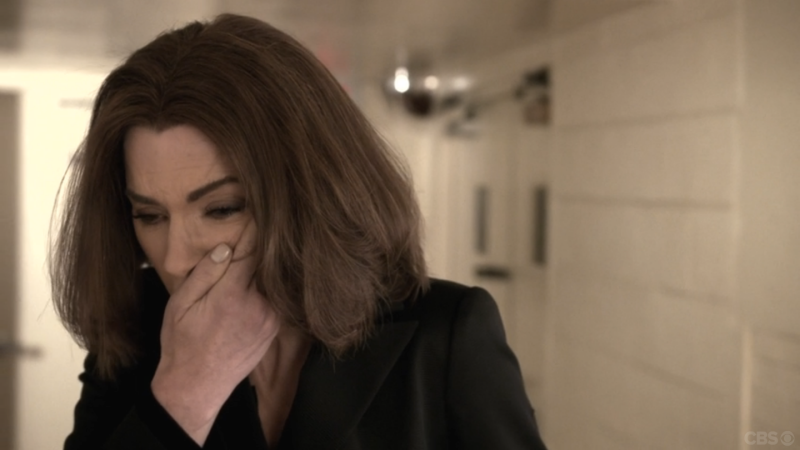

Diane slaps her in the face and walks away. Alicia doesn’t cry. In a performance that deserves to win [Julianna] Margulies her third Emmy for the role, she twists up her face and somehow finds strength. Yet through her reserve, there is vulnerability and fear. She doesn’t want to face the future alone, but knows she must.

Across the pond, Maureen Ryan for Variety also felt that the show had not earned its ending:

Your honor, the show asserted facts not in evidence. Many, many aspects of the final sequence of scenes in The Good Wife didn’t make any sense, on a plot level, on a thematic level or on a story level. Trying to pull off that slap and trying to make it fit with the contortions that preceded it was like watching a slick TV lawyer trying to get something dubious past a judge on a technicality by employing some fast talking and some very hinky arguments.

And then like a trial lawyer making her closing arguments, Maureen Ryan outlines at some length the chapter and verse of her objections. Joanna Robinson for Vanity Fair is much more sympathetic:

The Good Wife is a holdover from an earlier age of network—or really any—TV drama. While Alicia took her final bow in an era when the ice zombies on Game of Thrones and the sweaty zombies on The Walking Dead rule pop-culture, Alicia Florrick belongs to the time of Walter White, Don Draper, and the other stars of the golden age of the TV antihero. So it makes sense that her ending, like theirs, would be about moral decay and self-realization.

Joshua Rothman at The New Yorker is very good on the moral underpinnings of the series and its finale:

the show’s final episode took a different turn, reminding us that “The Good Wife” has never just been a show about power; it has also been about knowledge and the ways it can change an argument, a court case, a life… Alicia’s insistence upon the truth (for, it must be said, her own practical ends) was part of a larger debate, staged in the final episode, about the question “How much do you want to know?”

In an Atlantic piece titled ‘The Good Wife: Florrick vs the sisterhood’ Megan Garber is much more ambivalent about the show and its gender politics:

So while The Good Wife is “remarkable because it is a show where all of the real adults are women,” as The Hairpin’s Jennifer Schaffer had it, what is also remarkable is how little faith the show has had in the ability of those adult women to support each other, as colleagues who double as friends.

One last reading – here is the excellent TV critic at The New Yorker, Emily Nussbaum:

Over time, Alicia had gotten bolder and more powerful; she took less bullshit, became far savvier about her own desires, and learned to use the tools she grabbed along the way. She got less interested in being liked. I doubt that this finale will be beloved, either, because it didn’t reward the characters. But for me it was an ending that commanded respect. In life and in television, it’s difficult to resist the wishes of the wider world, but sometimes it’s the right thing to do.

Incidentally, we are promised the spin-off Diane Lockhart, so at least there’s one thing to look forward to in these dark, dark days.

Leave a Reply