Making ‘Drama…’, 5. The Style

John Wyver writes: I’m cautious about writing this post, which I intend – for the moment at least – to be the last in a series that has reflected on the production process of Drama Out of a Crisis; A Celebration of Play for Today. The first transmission has come and gone now and the film is starting its year-long life on BBC iPlayer. My previous posts are as follows: Starting out, The interviews, The archive and The graphics.

I’m cautious because self-justification is almost always an inappropriate strategy for programme makers, so I started these notes with no such intent. At the same time I want to expose something of the thinking — for good or ill — that went into producing the documentary. I’m cautious too because I fear that committing these thoughts to a blog will make the process seem far more pre-planned than in fact it was. Editor Todd Macdonald and I had some initial thoughts about what we would do, but much of what resulted came from a process of trying stuff out during a fairly lengthy remote edit and simply playing around (always respectfully, I hope) with the interviews that we haa shot and with the moving image archive and stills.

I hope I’ve stressed elsewhere just how much Todd contributed to the final film, and I want to acknowledge here too that such success as the film may have is to a significant degree thanks to him. My other deep debts are to the stalwart consultants Ian Greaves and Simon Farquhar, who offered a torrent of information and wonderful ideas across more than year of working on this (the Huw Wheldon lecture, for example, was Ian’s discovery); to designer Ian Cross, who imagined and achieved the film’s dazzling graphic style; and to the teams in BBC Archives and the BBC Photo Library, who made available a range of riches that still astonishes me, digitising materials when file copies were not immediately on offer and searching out obscure bits of off-air recordings that the system metadata had missed.

First thoughts

I began with a couple of very broad notions. One was that arts and archive documentaries, by and large, employed staid and static screen languages that had hardly changed in five decades. Their frames were invariably filled with single images and their intention was to give the viewer supposedly direct access to a world in front of the camera. Kenneth Clark was doing this more than fifty years ago, and Simon Schama is still doing much the same. In most arts documentaries made for television there is little or no attempt to acknowledge the processes of mediation, nor is there a concern to offer any sense of self-reflexive presentation. I thought that perhaps there might be alternatives to such an unthinking approach.

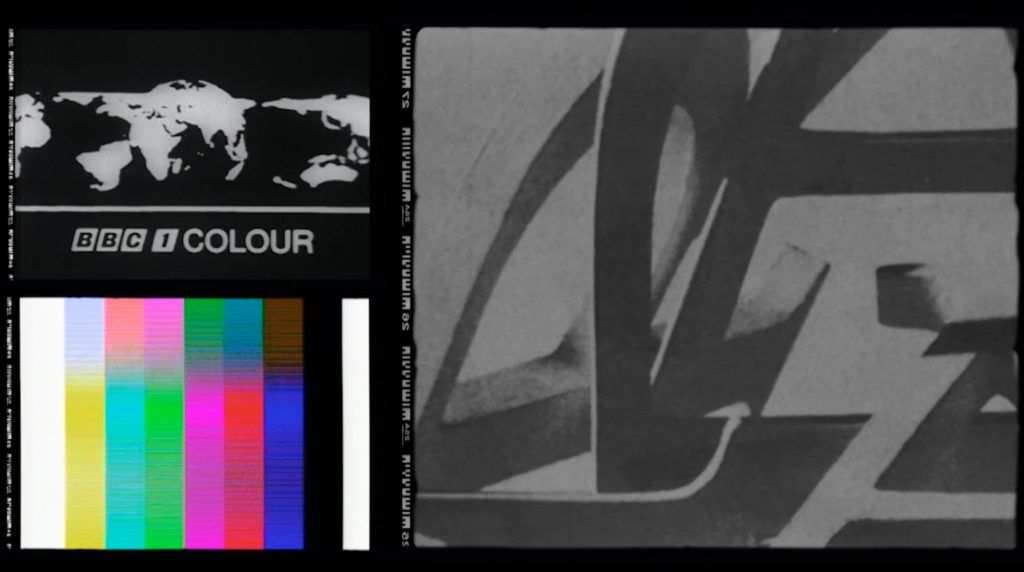

A second influence was what I identified earlier in the summer, in posts for this blog here, here and here, as the ‘language of lockdown’. I have been fascinated by the ways in which screen performance especially, but other media offerings too, have developed sophisticated split-screen languages, multiplying image streams within the overall frame and making creative juxtapositions across and within individual elements. Todd then explored some of the creative potential of these ideas in the series Anansi the Spider Re-spun that we produced with Unicorn Theatre.

In my posts I acknowledged a multitude of earlier but somehow still marginal explorations of the languages of split-screen. Indeed on Sunday I stumbled on the wonderful example below of the split-screen visualisation of a telephone call in the 1913 Danish film Ballettens Datter, shown online courtesy of the Danish Film Archive as part of Le Giornate del Cinema Muto from Pordenone. At the same time it seemed that, in large part because of the ubiquity of Zoom, Teams and similar interfaces in all of our lives, split-screen ‘spatial montages’ have now powered into the mainstream. Todd and I were intrigued to explore whether we could bring something of this style to the documentary.

Split-screens…

The split-screen sequences in the documentary serve, I think, a number of purposes. They permit us simply to reference a much wider range of archive material, and a much greater number of plays, than would have been possible in a straightforward linear edit of the same duration. They offer the possibility of compressing and perhaps even enhancing a lengthy archive sequence, as we do to relate the story of Shadows on our Skin and with the ending of The Garland.

They allow us to make connections between extracts and people, offering a variation on the conventional voice-over full-frame extract so often employed, as we do with Margaret Matheson and Alan Clarke in archive talking about Scum.

In some cases the split-screens suggest connections between people, as when we show an archive clip of Tony Garnett from some 25 years ago ‘listening” to Ken Loach speaking in 2020. This is then enriched with a sequence of side-by-side end title frames exemplifying the closeness of their professional relationship, to which Ken also refers in his interview.

And the split-screens allow us to adopt a playful attitude to the archive, as when we mirror an archive clip of Dennis Potter speaking either side of the mirrored title sequence of his Double Dare.

The film is visually richer, denser, more distinctive thanks to the split-screens throughout. And comparable contributions to this visual density are made by the radical editing of the interviews, about which I’ve already written, and by the graphics, again already discussed here.

… and self-reflexivity

Taken together, the split-screens and the other elements achieve a deliberately self-conscious or self-reflexive style. This is a film that constantly draws attention to itself and to the processes of its production. And this is complemented throughout by a focus on the materiality of making television, with a plethora of archive shots of the television studio in the 1960s and the 1970s (which are harder to track down than you might think) as well as the frequent employment of film flashes, video glitches and edge numbers plus the foregrounding of the studio in the interview set-ups and even the (somewhat clichéd) incorporation of clapperboard synching.

In his 1995 book Televisuality: Style, Crisis, and Authority in American Television, the scholar John T. Caldwell identified the appearance in television programming, and especially drama, of the time of what he dubbed ‘televisuality’. Earlier television, he suggested, had been content to transmit directly what was in front of a camera, whether that was a news broadcast, a sports event or a quiz show. But now television was starting to showcase its visual inventiveness and to move beyond a grounding in the idea of the relay.

In her exceptional study of the BBC’s 2005 classic serial Bleak House, Christine Geraghty neatly characterises Caldwell’s analysis:

Increasingly, style was upfront, designed to be noticed and enjoyed, the experience itself, not just something to support the content. And, although television drama was by no means the main plank of his argument, televisuality was to be found, not only in artistic dramas aimed at a specialist audience, but in popular television series such as Hill St Blues and Miami Vice. This interest in style as to-be-looked-at rather than to-be-looked through was a challenge to the classic serial’s more conservative tendencies throughout the 1990s.

To collapse a complex set of arguments, I was interested in the style of Drama Out of a Crisis as one to-be-looked-at rather than one to-be-looked-through.

Such a to-be-looked-at style is not, however, simply an exercise in decorative contemporaneity. Following the ideas of Bertolt Brecht and others (and again this is a huge debate), self-reflexivity can prompt a critical engagement with a subject, and ultimately that was my aim with the documentary. I hoped that Drama Out of a Crisis would be enjoyable, and that the extracts would prompt surprise and even shock as well as nostalgic pleasure, but that ultimately the film’s to-be-looked-at style, in addition to being pleasing and distinctive, would provoke viewers to question each extract and every statement. Which surely should be the aim of any half-decent documentary.

And there… having said that I wanted to avoid self-justification, that’s exactly what I’ve ended up doing.

Delighted to read this Tweet from @waltydunlop this morning:

‘Found myself actively engaging with the split-screen on this last night, attention constantly refocusing depending on what was happening. Exhilarating way to pack as much on-screen as possible. It felt like I was watching less passively than I might have, if that makes sense.”

I responded with the line from Keith Barron’s character in Dennis Potter’s Only Make Believe (he’s called Christopher although no-one ever recalls that), but without the sarcasm:

‘My ideal audience.’

That tweet from @waltydunlop definitely resonates with me – it was a very active viewing experience – it felt exploratory and it was also impossible to ignore the fact that we were only – and could only be, by the very nature of the strand’s expansiveness – snippets and clips of each play. I think this is a good thing: it meant that as a viewer we were under no illusions that the doc was supposed to tell us all we needed to know about Play for Today or present a straightforward and comprehensive narrative. Left me eager to watch more and research further! I will revisit it countless times, no doubt.

I did think the way the participants handled the clapper was wonderfully indicative of their personality!

We really didn’t expect that, Christine, but when we looked at all of those moments together they did remarkably revealing. Thanks.