Masterpieces at home 3. [Updated]

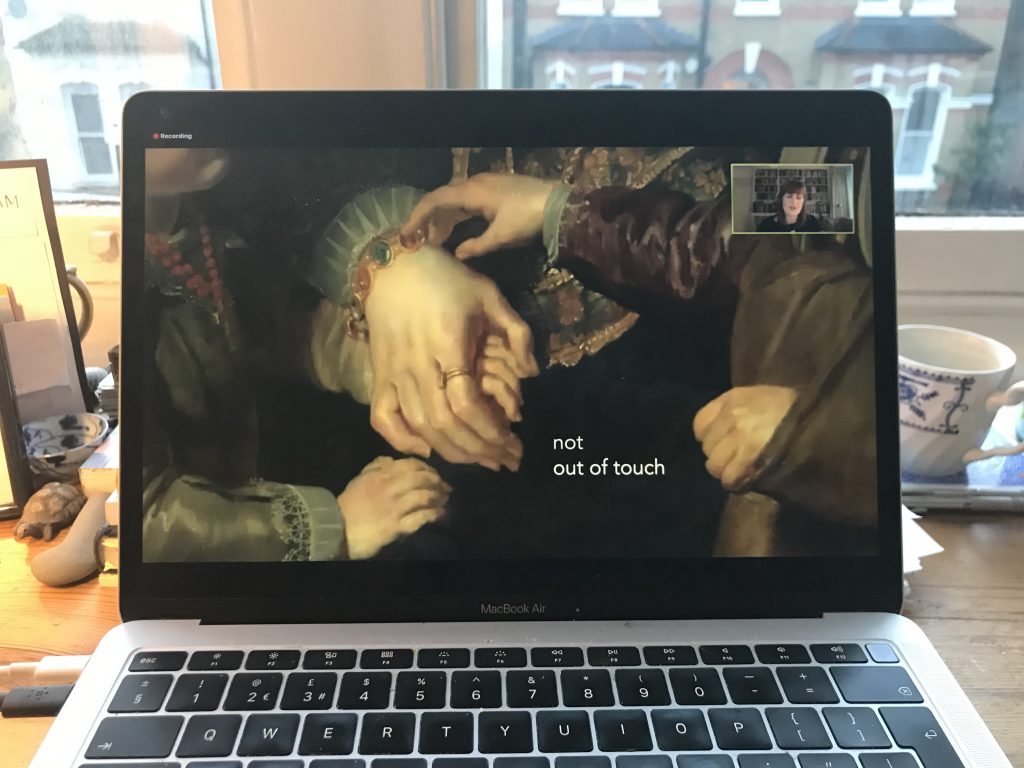

John Wyver writes: Yesterday was #MuseumFromHome day, which was co-ordinated as part of the very welcome Culture in Quarantine initiative from BBC Arts. Developed alongside the Museums in Quarantine films, two of which I wrote about on Tuesday, here was lots of activity on a webstream and a dizzying array of tagged Twitter activity. In the midst of all the buzzy-ness I elected to participate in two other extended offerings: a Look Slowly, Think Artfully webinar from the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, and the first Open Courtauld Hour (above) offered by the Courtauld Institute of Art. The first, I decided part way through, was not for me, but I got a great deal from the Courtauld Zoomcast, and I’m looking forward to the next three on the Thursday evenings to come.

The NGA webinar was built around close looking at Joan Miró’s 1921 The Farm, which is a jewel of the gallery’s holdings. Led by the education department, this drew hundreds of registered participants to a Zoom event which combined a directed channel with an open chat function to which we were all invited to contribute. I found that I could neither keep up with, or indeed add to, the ceaseless chat postings nor focus appropriately on the quadrant by quadrant slow looking that we were prompted to undertake. Nor did the tone quite work for me and, reader, I made my virtual excuses and left.

There was no technological facilitation of participation in the Courtauld cast, which was unapologetic online broadcasting. The informal and accessible address of the contributors, however, very successfully encouraged us to become involved by reflecting on the artworks and ideas being put forward. I also enjoyed the inevitable uncertainty of switching Zoom hosts, calling up screen sharing, and occasional broadband slowdowns. Somehow this glitchiness, which was sufficiently contained so as not to become irritating, offered the kind of cracks for me to mentally wriggle into that television’s near-perfect surface invariably smoothes over.

Hosted by the Courtauld’s head of research Alixe Bovey (above, bottom), who has past form as a television presenter (and who I should say I count as a friend), the hour drew together short talk-and-slides presentations from Alixe herself, deputy head of the Courtauld Gallery Barnaby Wright (above, top left); Caroline Campbell (above, top right), who is director of collections and research at the National Gallery, and fashion historian Lorraine Smith, co-founder of the The Underpinnings Museum, a rather wonderful (and as far as I was concerned, before this unexplored) online collection of lingerie.

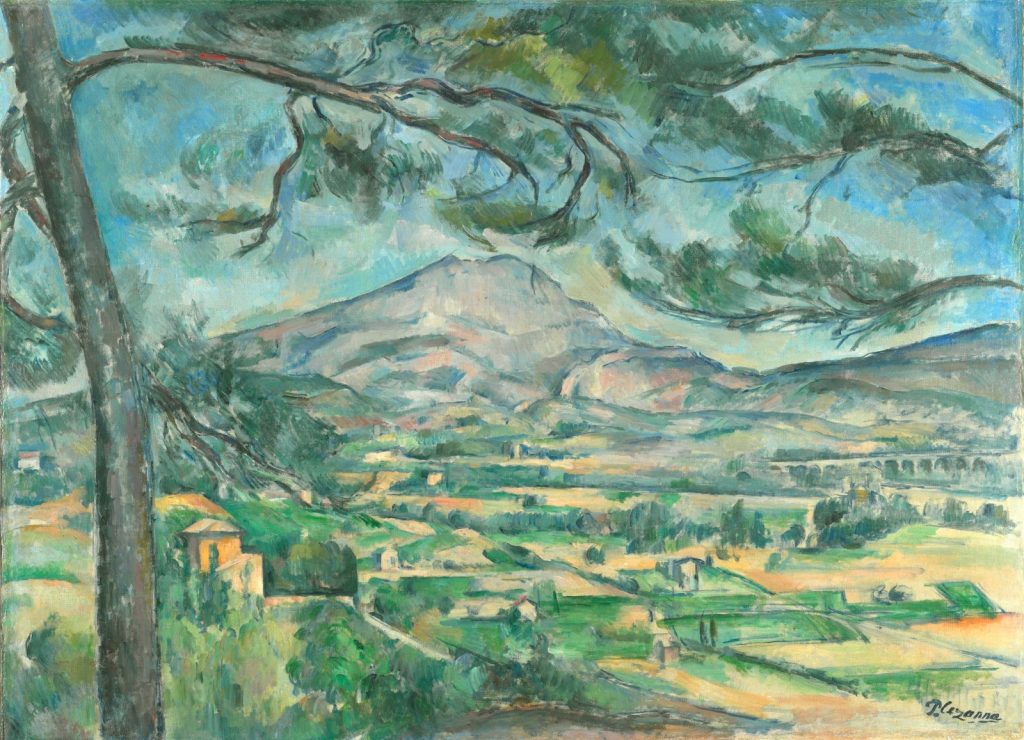

At the close poet Shagufta K Iqbal (above) contributed a gorgeous response to Cézanne’s Montagne Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine, c. 1887 (below), and his The Card Players, both from the Courtauld’s collection.

Alixe spoke about the extraordinary creativity prompted by the lockdown and considered the ways in which the events of the past weeks have prompted new ways of looking at familiar artworks. Barnaby Wright considered the enhanced focus now on the importance of digital content from cultural organisations, and he (rightly) celebrated the Courtauld Gallery’s virtual tour. Unfussy, immersive and zoomable to a remarkable degree, this was created some eight years ago (and thus lacks some of the digital bells and whistles of later projects), but in the first days of the lockdown it saw a 2000% increase in the numbers of those accessing it. He suggested that this creates a contemplative space online for looking and thinking.

As a sidebar, it’s well worth taking a look at Michael Alexis’ data-driven blog post at Museum Hack, ‘People don’t want virtual museum tours; do this instead’:

For a few days in March, 2020, the world focused its attention on virtual museum tours. This attention was driven by museum closures, major media coverage, and a mighty social media effort by museums to offer an online experience to audiences. And then, just as quickly, the attention disappeared and museums were left in what might be the greatest struggle for short-term relevancy they have ever faced.

At the same time Michael Alexis also suggests other ways in which museums can engage fruitfully with their audiences, including quarantine date ideas:

[M]useums already exist as a place that people go on dates. You can reach this interest online by offering digital experiences that match the market’s interests. Data shows that people are looking for fun, cheap and romantic dates; in that order. Fun leads the other two by a factor of 2x, so I would recommend focusing on that.

Back at my own date with the Courtauld Open Hour, Lorraine Smith engagingly addressed, with appropriate references to the scholarly literature, the key question of whether – and why – we should get dressed during lockdown. She came to the conclusion that fancy fashion in isolation can help lift your mood and improve your overall well-being.

The terrors and comforts of touch

The contribution I especially valued was that from Caroline Campbell, who looked back to the only other time during the history of the National Gallery when its doors had been closed. This was at the start of World War Two, when the paintings were evacuated (mostly) to caves at Manod in Snowdonia.

(I was fortunate enough to visit the site, and to access the caves, which in late 2017 still had some of the racks on which the artworks were hung, during the pre-production of Robin Friend’s dance film collaboration with Wayne MacGregor for Performance Live, Winged Bull in the Elephant Case (2018). This remarkable production, which was partly filmed in the National Gallery (and sadly not at Manod, which was deemed too dangerous), is currently available on BBC iPlayer here.)

During the early years of the war, once it re-opened, the largely empty National Gallery was the site of the astonishingly popular lunchtime concerts, many of them given by the indomitable pianist Myra Hess (and documented in Humphrey Jennings and Stewart McAllister’s poetic documentary, Listen to Britain, 1942; an extract can be seen here). The director of the gallery, Sir Kenneth Clark, asked in a poll which single work the public would like to see brought back first from Wales to be put on display for a month. Apparently to K’s surprise, the selection was Titian’s Noli me tangere, c. 1514 (the usual translation is ‘touch me not’).

What did this great painting of Christ and Mary Magdalene in the garden of Gethsemane mean to people in a time of crisis nearly 80 years ago, and what can it mean to us now, at a moment when touch has become terrifying? Caroline Campbell’s questions echo with those posed earlier by Alixe Bovey, who had included in her presentation a detail from another great early modern masterpiece.

On which theme, yesterday the BFI and EVCOM (Event & Visual Communications Association) released this new short made by director Tim Langford in support of NHS Charities Together (you can donate here), featuring Iain Glen reading Michael Rosen’s poem ‘These Are the Hands’ together with archive footage from 1948 and since:

The Courtauld said last night that they intend to post the recording online, and when they do the link will be included here. And if you would like to join one of the three forthcoming Open Hours, you can sign up here – for free.

See also Masterpieces at home 1. and Masterpieces at home 2.

Update: Courtauld Open Hour 1 is now available on the Courtauld’s Youtube channel here:

Leave a Reply