MoMA marvels

The Museum of Modern Art in New York recently unveiled an exciting, extraordinary and exemplary archival project, ‘Exhibition history’, that is putting online for free and unrestricted access thousands and thousands of installation photographs, press releases and – most remarkable of all – hundreds of out-of-print catalogues. I have picked three initial favourites below, but it’s important to recognise just how astonishing an achievement this is – and how it makes available unparalleled access to the history of one of the world’s great cultural organisations. Perhaps Tate might take a look?

Reporting the initiative for The New York Times, Randy Kennedy writes:

The digital archive project will include almost 33,000 exhibition installation photographs, most never previously available online, along with the pages of 800 out-of-print catalogs and more than 1,000 exhibition checklists, documents related to more than 3,500 exhibitions from 1929 through 1989. (The project, supported by the Leon Levy Foundation, will continue to add documents from more recent years and also plans to add archives from the museum’s film and performance departments.)

Britain at War was an exhibition that ran from 23 May to 2 September 1941 overseen by Sir Kenneth Clark. A cultural strand to the diplomatic campaign to draw the USA into fighting with the Allies, the show as reflected in the catalogue was strikingly diverse, including photographs, posters and cartoons as well as paintings and drawings.

Most of the works had been previously shown at an exhibition of war artists’ work at the National Gallery in London, and many are illustrated in monochrome images. There are key canvases from the First World War, including ones by Edward Wadsworth, Eric Kennington and Paul Nash, as well as recently completed (and, to, at least, unfamilar) paintings by Evelyn Dunbar, Barnett Freedman, Keith Henderson and the remarkable The Elms, 1940, by John Armstrong (below), now in the Bristol Museum, Galleries and Archives collections.

The catalogue features a poem by T.S. Eliot and an essay by the eminent critic Herbert Read, which he concludes almost apologetically in this way:

It may be that the general effect will strike the American visitor as tame or subdued, as too quiet and harmonious for the adequate representation of war. It must then be remembered that though the English are energetic in action, they are restrained in expression. Our typical poetry is lyrical, not epical or even tragic. Our typical music is the madrigal and the song, not the opera and the symphony. Our typical painting is the landscape. In all these respects war cannot change us; and we are fighting this war precisely because in these respects we refuse to be changed. Our art is the exact expression of our conception of liberty: the free and unforced reflection of all the variety and eccentricity of the individual human being.

As well as the catalogue being online (and downloadable as a .pdf), MoMA has posted the full exhibition checklist, the original press release and some 60 installation photographs – which together allows you to pretty much imaginatively recreate a virtual visit to the show, albeit one still in black and white. Extraordinary.

The Machine, as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age is recognised now as one of the key exhibitions of the 1960s. Curated by Pontus Hultén, it ran from 27 November 1968 to 9 February 1969. Hultén’s Foreword begins with these words:

This exhibition and its catalogue make no attempt to provide an illustrated history of the machine through the ages. It is a collection of comments on technology by artists of the Western world.

Although the pages are frustratingly out of order in the downloadable .pdf, the catalogue is a treasure trove of material about artworks from Leonardo da Vinci to Nam June Paik, as well as related material like Rube Goldberg drawings and stills from Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times, 1936. And again there are numerous installation shots which give a strong sense of how it felt to visit the galleries nearly 50 years ago.

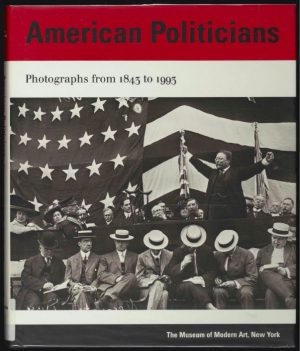

American Politicians: Photographs from 1843 to 1993, an exhibition of around 175 images that ran from 6 October 1994 to 3 January 1995, feels particularly timely this week. Online, the museum describes it as

the first comprehensive exhibition to examine the ways in which photography has both recorded and shaped the image of the American politician, demonstrates how advances in photographic technology and distribution have altered our perceptions of politicians and the democratic process. This exhibition ranges from formal, stately portraits of Abraham Lincoln and John Quincey Adams through examples of today’s manufactured “photo opportunity.”

The long out-of-print catalogue by Susan Kismaric is terrific, and it’s simply a joy to be able to download it in full and for free. Included is the particularly pertinent (and poignant) image by Larry Fink, ‘Hillary Rodham Clinton and Pat Schroeder, Washington, D.C. May 1993’.

Leave a Reply