Playing Lear

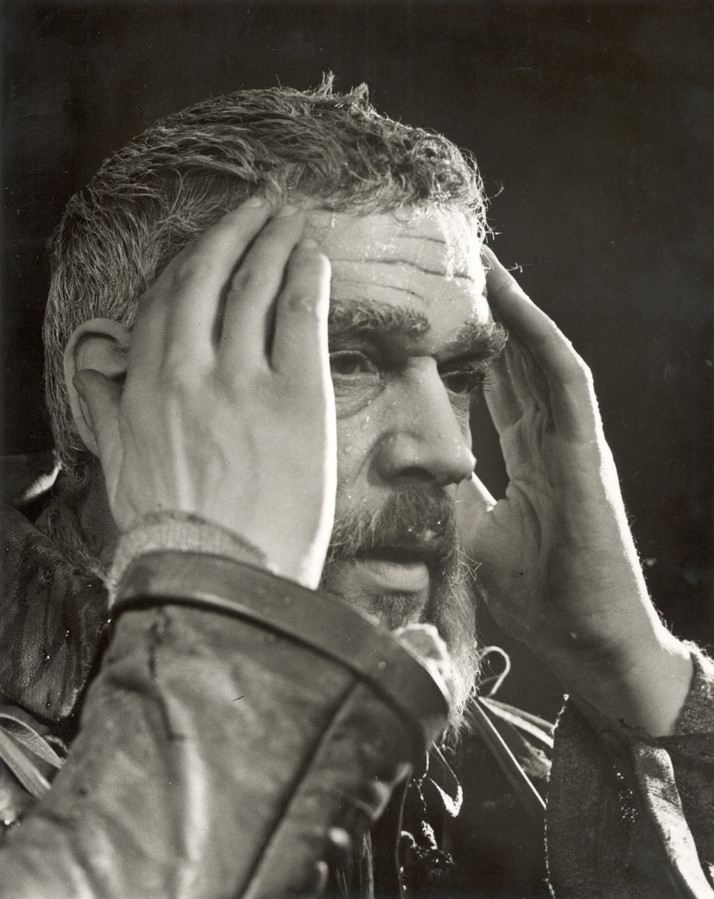

On Wednesday this week RSC Live from Stratford-upon-Avon broadcasts Gregory Doran’s production of King Lear to cinemas across Britain. As preparation for this, my work as producer has meant that I’ve watched the staging half a dozen times now – and on each occasion it seems to me richer and deeper and more moving. Antony Sher plays the king and gives, to my mind, a fiercely intelligent, subtly complex performance that I feel privileged to be seeing at close quarters. Complementing him is an exceptional cast including David Troughton, Antony Byrne, Paapa Essiedu and Natalie Simpson. And the production is strikingly visual too, with Niki Turner’s vivid, often sumptuous design and Tim Mitchell’s accomplished lighting. If you can book a ticket for Wednesday I don’t think you’ll regret it.

We’re opening the broadcast with a brief montage of photographs of distinguished actors who have played Lear at Stratford, beginning with John Gielgud in 1950. And as background to all of this I have been reading Jonathan Croall’s terrific recent book for The Arden Shakespeare, Performing King Lear: From Gielgud to Russell Beale. (I should note I’m also working on a book for Arden.)

Drawing on a mix of contemporary reviews and revealing new interviews, in Performing Lear Jonathan Croall discusses the ways in which King Lear as character and as drama has been interpreted across history, and especially since John Gielgud played the first of his four Lears at the Old Vic in 1931. The book, which is clearly the result of extensive research, is full of insight, theatrical lore and anecdotal detail (although it has one regrettable absence, of which more below). Included are the following comments about earlier Lears in Stratford:

On John Gielgud, 1950: this was the great actor’s Stratford debut, in a production by Anthony Quayle, and the critic J.C. Trewin wrote, ‘King Lear is an Ancient Monument, but in the early stages Gielgud behaves like a guide who is showing us around… Until the end the actor, intellectually commanding, illuminated the part from without rather than from within.’

On John Gielgud, 1955: the actor persuaded director George Devine to commission designs from the celebrated American/Japanese sculptor Isamu Noguchi. As Croall writes,

Noguchi produced a set of startling abstract and geometric designs, including egg-forms, triangular caverns, bright-coloured moving screens, airborne prisms and a large floating wall… However, Noguchi had never designed costumes before, neither could he draw… Gielgud, his face surrounded by dense white horsehair, wore a crown resembling an upturned milking stool, carried what looked like a hearth-brush, and was trapped in a cloak full of holes, which symbolically grew larger as Lear’s mind disintegrated.. [He] was variously compared to the Wizard of Oz, a gruyere cheese, and a Henry Moore sculpture, while Emlyn Williams dubbed him “Gypsy Rose Lear”.

On Charles Laughton, 1959: tempted to Stratford to play both Bottom and Lear by young tyro Peter Hall, the ageing Hollywood actor failed to impress in the tragic role. Hall later wrote,

At another time, and if he acted the part in an intimate space, he might have been one of the great Lears. The pathos and ribaldry of his unhinged mind were certainly extraordinary. But in the storm he became, on the huge stage of the Stratford theatre, an aging actor whose voice had weakened, and who no longer had the equipment that was needed. He had been away too long. Playing Shakespeare is like athletics, you have to keep in training.

On Paul Scofield, 1962: for the 37-year-old director Peter Brook (who subsequently made a film of King Lear with Scofield), King Lear is a play about sight and blindness, ‘what sight amounts to, what blindness means – how the two eyes of Lear ignore what the instinct of the Fool apprehends, how the two eyes of Gloucester miss what his blindness shows.’ Croall is especially fascinating on the rehearsal process of this legendary production, detailing the ambivalence on the part of several of the cast towards the techniques of improvisation that Brook favoured. Later, to help them deal with the grimness of the play, Scofield and Alec McCowen (playing the Fool) would stand in the wings before the storm scene and sing Arthur Askey’s song, ‘I’m a busy, busy bee’.

On Michael Gambon, 1982: in an interview with Croall, director Adrian Noble recalled,

[Lear] can be quite unrewarding as a part. I thought Michael absolutely astonishing from the Dover cliff scene until the end, and very moving. The first half was trickier for him. It’s absolutely unremitting, and almost unplayable: the pain is so great the vocal demands so huge. It gets actors down a lot, because it magnifies your failures. I’m not saying that Michael didn’t do it well, but the journey to madness is very hard to play. The dreadful break with Cordelia, the cursing of Goneril – these are difficult areas for an actor, because they have to do and say really toxic and horrible things.

On Robert Stephens, 1993: Stephens was seriously ill throughout the run, dealing with problems with his liver and kidneys, and sometimes missing performances. David Calder, who played Kent, recalled, ‘It was either genius or awful. When he could remember the lines he could be absolutely brilliant. At other times we were on the verge of taking the audience home for breakfast.’ One pertinent response to the production apparently came from RSC President Prince Charles, who after seeing the production remarked, ‘There is one thing I’ve learned from this play: don’t abdicate!’

And now for my disappointment about Jonathan Croall’s wonderfully engaging book… his research encompasses many of the British theatre’s post-war productions of King Lear, including presentations at the Tivoli theatre in Dublin (with Timothy West, 1992) and the Southwark Playhouse (Oliver Cotton, 1996), but he nowhere considers (nor I think even mentions) any of the television productions of the play.

Given that the performance history of King Lear on the small screen has included, among others, Patrick Magee (for ITV schools television, 1974), Michael Hordern (both for BBC Play of the Month, 1975, and for The BBC Television Shakespeare, 1982, on both occasions directed by Jonathan Miller) and Laurence Olivier (ITV, 1983), this omission seems egregious. (Richard Eyre’s 1998 National Theatre version with Ian Holm, which was recorded by the BBC, is considered as a stage production.)

For me, and for many among their very large audiences, these broadcasts would have meant just as much as any stage productions that they might have seen. Not to discuss them reinforces a hierarchy of media that assumes the theatre to offer a superior experience to television. That grump aside (and the unfortunate mis-spelling throughout of Antony Sher), I heartily recommend Performing Lear as accessible and immaculate scholarship from which practitioners and audience members alike will derive much.

Lead image: Antony Sher as King Lear and David Troughton as Gloucester; photo Ellie Kurttz, © RSC; images of Gielgud, Laughton and Scofield by Angus McBean, © RSC.

I’ve been searching for, but so far unable to find, the 1975 BBC Play of the Month version of Lear, with Michael Hordern. The 1982 version is available as part of the BBC Shakespeare Collection, and I have that, but would you happen to know if the 1975 version was every released, or how else I might be able to view it? Many thanks