Screening the RSC, 5.

John Wyver writes: So it’s the official publication day for Screening the Royal Shakespeare Company: A Critical History. My thanks to The Arden Shakespeare for taking this on, to Gregory Doran and other colleagues at the RSC for all their support, and to numerous other scholars, archivists, friends and more for assistance in making this real. I am thrilled to see my book in print.

If you are interested to read a substantial element of it, this link will take you to a preview of the Introduction and Chapter 1…

In addition, I have scratched out four previous posts highlighting elements of the Introduction to the book and of its first three chapters: 1. Beginners 1910-1959; 2. Television Times, 1910-1959; and 3. Making Movies, 1964-1973. Today, I am finishing the series with an outline of what is in the final three chapters.

I know that, because of the demands of academic publishing, the hardback price for the book is unaffordable. But I hope that there will be a paperback next year – and a good reception will help that process. In the meantime I would be delighted if you would consider recommending it as a library purchase.

Chapter 4: Intimate Spaces, 1972-82

Having left. in the previous chapter, the RSC struggling at the end of the 1960s with the fallout of its flirtation with Hollywood, this chapter begins with the arrival of Trevor Nunn as artistic director. I discuss Nunn’s screen work with the company, which includes a delightful The Comedy of Errors, 1977 (below); the magnificent Macbeth, 1979, with Judi Dench and Ian McKellen; and the fairly dreadful (and rarely-seen) Three Sisters, 1981. The chapter is also concerned with the ways in which screen adaptations of the company’s work respond to the impact on the RSC of the shift during the 1970s to smaller spaces – including Buzz Goodbody’s work at the original The Other Space – new ways of working and changing ideas of what theatre was and might be.

The company’s negotiation of the fundamental cultural and social changes during the decade culminated in one of the glories of the RSC’s work, both on stage and one screen: The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. Commissioned as Channel 4’s very first independent production, this remains a hugely enjoyable screen adaptation (see below, which remains one of my favourite scenes in the RSC’s adaptation history), and is all the more interesting because there is also a feature-length edition of The South Bank Show chronicling the production of the stage version.

The South Bank Show at the end of the 1970s and into the 1980s made several richly interesting programmes with the RSC, including a pair of programmes titled Word of Mouth that are stimulating masterclasses in verse speaking, and a follow-up series, Playing Shakespeare, that has John Barton as host treating similar material in more detail.

Chapter 5: Toil and Troubles, 1982-2002

In the 1980s and ’90s, television and the cinema were far less significant for the RSC. These were the years when the company moved in to the purpose-built facilities at the Barbican, and when they later abandoned them. The move should have provided a greater element of stability, but key decisions associated with the move eventually led to challenges to the company’s very existence. The screen memories of this time are fewer and less vivid, but the moving image traces of the company were about to be radically expanded – even if the shifts were, as to a large extent they have remained, essentially invisible.

One of the aspects of the book that pleases me the most is that I have not restricted the discussion to conventional adaptations, but have tried to explore the production contexts and aesthetics of less mainstream screen productions: the extracts of performance included in documentaries and review programmes, the single-camera archival recordings made by the RSC as production records, and what we can regard as ‘paratexts’, the trailers, press kits and extracts made for education. Each of these ‘captures’ elements of a production, but they have been little-studied and have a precarious archival existence. We should take this kind of material far more seriously than we do. Here’s one of the earliest RSC trailers, from 2010, that continues to circulate on Youtube:

Chapter 6: Now-ness, 2000-18

At the end of Chapter 5, I enter the story I’m relating, since I discuss my failed project – developed initially by the BBC – to make a screen version of Michael Boyd’s great History plays cycle. As I recount, I did a great deal of work on this before the idea was gazumped by Sam Mendes and the first series of The Hollow Crown.

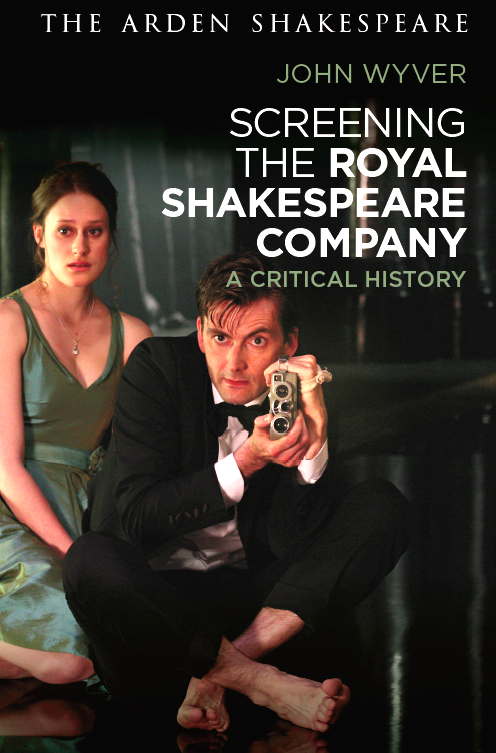

I take an even more central role in Chapter 6, which chronicles my work with Gregory Doran on the television films of Macbeth, 2000, Hamlet, 2009 (header image by Ellie Kurttz © RSC), and Julius Caesar, 2012. I also relate how, before the BBC committed to Hamlet, we put together the framework for a live cinema broadcast of the production, a year ahead of the first NT Live. The chapter also explores the RSC Live from Stratford-upon-Avon cinema broadcasts that the company has produced since 2013.

I end with a plea for the RSC moving image archive to be cherished more than it perhaps is at present, and for it to become ‘an accessible, usable source for active, creative interpretations, drawing together the companyt’s histories with its present practices and its future possibilities.’

And finally – I mention this in a footnote, and it exemplifies how a production can have an unexpected afterlife – here’s the climax of series 2 of The West Wing using Stephen Oliver’s patriotic song from Nicholas Nickleby…

Leave a Reply